If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off… no matter what they say.

Barbara McClintock, American scientist and cytogeneticist

When we say 'biologist', what do we mean, exactly? Marine biologists? Plant biologists? Maybe we're only considering zoologists... or could we consider those marvellous minds generally associated with other profound disciplines where biology plays only a minor role? Most people, when quizzed about who is the most famous biologist of all time (or zoologists, naturalists, and so on), inevitably toss out Darwin's name. Those who have a particular love for the sea might invoke Jacques Cousteau. Besides being the most renowned oceanographer, he was the world's first marine conservationist. A biology major or history major may know of a few more names - familiar to all but possibly in a different context. Let's see how your list and ours match up, shall we?

| Name | Born–Died | Nationality | Major Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotle | 384 BC – 322 BC | Greek | Systematic study of living organisms; foundations of biology |

| Hippocrates of Kos | c. 460 BC – c. 375 BC | Greek | Established medicine as a profession; clinical observation |

| Galen of Pergamum | c. 129 – c. 216 | Greek / Roman Empire | Anatomical and physiological research; shaped medical science |

| Antonie van Leeuwenhoek | 1632 – 1723 | Dutch | First to observe microorganisms; “Father of Microbiology” |

| Carl Linnaeus | 1707 – 1778 | Swedish | Developed binomial nomenclature; “Father of Modern Taxonomy” |

| Charles Darwin | 1809 – 1882 | English | Theory of evolution by natural selection |

| Louis Pasteur | 1822 – 1895 | French | Germ theory of disease; pasteurisation and vaccines |

| Gregor Mendel | 1822 – 1884 | Austrian | Discovered laws of heredity; “Father of Genetics” |

| Barbara McClintock | 1902 – 1992 | American | Discovered transposable genetic elements (“jumping genes”) |

| Rachel Carson | 1907 – 1964 | American | Exposed pesticide dangers; inspired modern environmentalism |

| James D. Watson | Born 1928 | American | Co-discovered DNA’s double-helix structure |

| Jennifer Doudna | Born 1964 | American | Co-invented CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology |

Charles Darwin

This English naturalist, biologist, zoologist, and geologist hardly needs any introduction. Even those with no love of science know that he made significant contributions to our knowledge of evolution. Charles Darwin himself was not a man given to humor or whimsy. He was a rather serious lad who often accompanied his father on medical rounds. Robert Darwin, his father, was a well-positioned society man. He might have made a name for himself in medicine, but was instead content to serve the genteel community of which he was a part.

He expected his son to follow him into the medical field, but young Charles had no stomach for surgery. He also found the university lectures boring, so he did not study very hard. However, he joined a Natural History debate group, where he met British zoologist/anatomist Robert Edmund Grant. That worthy had the temerity to openly praise evolutionary ideas, something that utterly shocked the impressionable young Charles. He was astounded that his mentor dared to express his embrace of evolutionary theory so openly. The theory itself fazed him little; he had read similar thoughts in his grandfather Erasmus' notebooks.

Soon, Charles Darwin was in a quandary. University lectures failed to hold his interest in natural history. He was drawn to plant classification—an early exercise that would later lead to his penchant for taxonomy. His father grew ever more frustrated with his cavalier attitude towards medicine. A change was coming. It would send Darwin around the world and inform future generations on evolutionary theory and, ultimately, his masterpiece, The Origin of the Species.

Gregor Mendel

Unlike the naturalist/biologist/zoologist we just discussed, Johann Mendel's father was neither well-to-do nor a medical man. He was a farmer who eked out a living in (what is now known as) Czechia, but he had high hopes for his only son. They just weren't the hopes the son had for himself. Mendel loved physics and math, and he excelled in both subjects... when he was in school. Unfortunately, his rather delicate constitution forced him out of school for long stretches - once, while enrolled at the University of Olomouc, he absented himself for an entire year.

His frequent illnesses added a financial burden to the family. They were having a hard time paying for his schooling; his long breaks meant that he would need even longer to complete his studies. That's why he entered the monastery. It was an effective way to get an education without having to worry about paying for it or for food and other life necessities. Stress and anxiety were making his already frail condition worse; he could hardly afford to worry where his next meal would come from and still excel in his studies.

He was given the name Gregor when he entered the abbey and, true to their word, the Augustine Order saw to his education. They even covered all his expenses while he was studying at the University of Vienna.

Were Mendel's studies in Vienna a waste of time and money? No, of course not! Studying is never a waste of time or money! However, it's hard to measure how much they helped to shape his work in cross-breeding peas to discover the rules of heredity that, to this day, underpin the science of genetics. Indeed, Gregor Mendel is famous for being the Father of Modern Genetics.

Galen of Pergamum

While Mendel was generally known as a quiet and amiable man, Galen was anything but. With his vile temper and arrogant attitude, especially toward his fellows in medicine, Galen lived in genuine fear that somebody would murder him. At one point, he fled Rome before he could meet a grisly death.

As unpleasant as cussing and screaming at people is, he came by his attitude honestly - history shows he mainly abused competitors because of their incompetence. Today, Galen is considered Antiquity's most accomplished medical researcher. Scientists worldwide are still building on his discoveries today. What discoveries, you ask? They include:

As mentioned before, Galen was a rather rude and arrogant man, despite being a genius. He knew he couldn't cut dead people open - human dissection was taboo at that time. However, there were no laws against cutting animals open, no matter whether they were alive or dead. That, he did fairly regularly.

In one notable example of such, Galen demonstrated the function of the larynx... by cutting a pig's throat open and, as it squealed, he severed its vocal cords. The poor animal was still in a frenzy, but it just wasn't making any more sounds. He replicated this brutal experiment several times with countless specimens, severing motor nerves and observing their inability to move the corresponding limbs.

For all of that brutality and callousness, today's scientists would be brought up on charges if they operated in that manner. Galen must have had something resembling a heart. His initial experiments were done on monkeys. He reasoned their anatomy must be identical to humans' because the species were so similar, that, without knowing a thing about DNA!

However, he found that, as he prepared to cut open a live monkey, that too-human face spooked him. Galen draped a cloth over the animal's face and carried on, but that was the last time he experimented on a monkey.

Hippocrates of Kos

This physician from the Classical Greek era is known worldwide as the Father of Medicine. Strangely enough, though, the phrase most commonly attributed to him was not his at all.

The first known use of 'first, do no harm' was in the 17th Century, by the British physician Thomas Sydenham. He most likely translated it from Latin —primum non nocere —indicating that it could not have originated with the most famous doctor in history. That edict doesn't even appear in the Hippocratic Oath.

Initially, Hippocrates was an adherent of the Four Humors philosophy of medicine - the belief that people's bodies contained four specific liquids whose ratios must remain in balance to ensure good health.

He later abandoned those beliefs, instead advancing the radical idea of patient well-being, even as they suffered through sickness.

Contrary to other physicians of his time, Hippocrates emphasized prognosis rather than diagnosis. That novel concept grew out of his theory of 'medical crises', points at which the body's natural defences would overwhelm the illness (and cure itself) or the disease would invade more cells than the body has to fight it off. That overly simple outline of Hippocrates' medical philosophy makes it easy to see why he is still revered as the Father of Medicine. It represents the essence of medical care.

Aristotle

If this writer were allowed, I would confess that Mendel elicits the most sympathy, Galen the most ire, and this one is my favorite famous biologist of all. Unlike the other biologists featured in this article, Aristotle did not have a firm hand to guide his studies. His parents died when he was barely a teenager, and after a few years in the care of his brother-in-law, he was shipped off to Athens to study at Plato's Academy.

In those times, fathers dictated what one studied. Aristotle, absent a father - or even a father figure - was unbound by convention and untethered from any directional tiller. In short, he was allowed to study anything he chose... so he decided to study everything.

His tenure at the Academy ended after nearly two decades. He set off for the island of Lesvos with a pupil in tow to study every life form - plant, marine, and land animals. Aristotle was primarily an empiricist, but his works indicate that he sometimes took an active part in discovery. His diagrams of specimens' innards are far too detailed and accurate to have been merely thought up. Some of the theories he constructed and conclusions he drew make it clear that his work was not just a series of thought experiments about living things.

Many assume his focus was primarily on zoology, with a possible second on marine life, but given that his students' surviving work mainly discusses plants and their particulars, we have to believe that Aristotle was completely impartial. He would study anything that stood still long enough for him to study.

Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson was a trained biologist and gifted writer. She began her career at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries before she started looking at the relationship between people (and their actions) and the planet. In 1962, she published Silent Spring, which exposed the environmental impacts of pesticides such as DDT. At the time, the chemicals were seen as scientific triumphs. Still, Carson's research raised concerns about them and was ultimately deemed highly controversial. There was a backlash from the chemical industry, which launched a campaign to discredit her.

Ultimately, her work (and approach) helped inspire a global environmental movement. Within a decade of her death, governments around the world began banning or restricting the use of harmful pesticides. Her research and work helped pave the way for the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. To this day, she remains one of the most influential biologists of the 20th century, something you can learn more about in biology courses here on Superprof.

Barbara McClintock

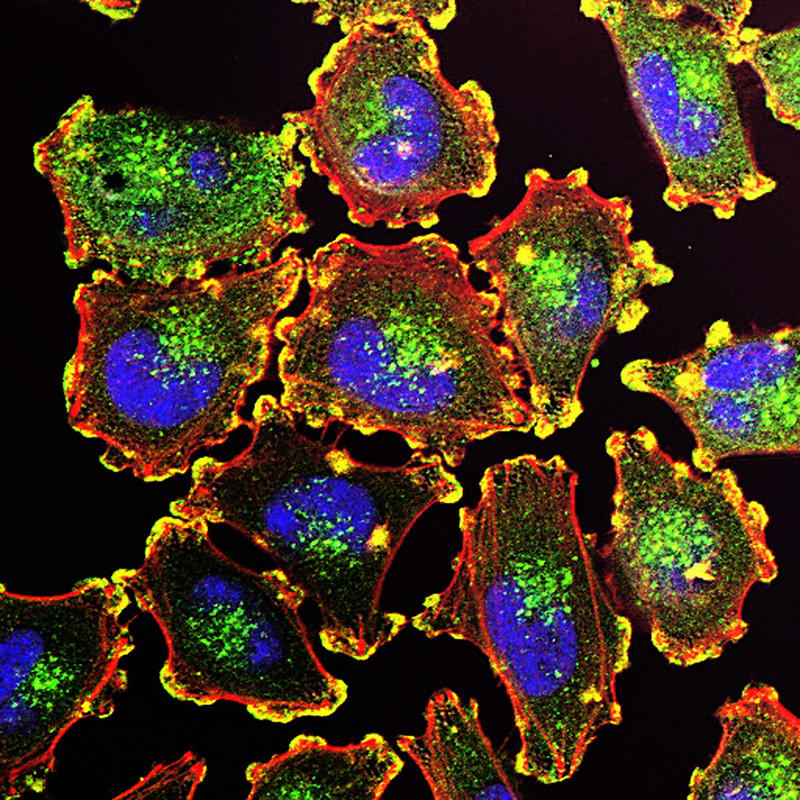

Barba McClintock helped us understand the genetic makeup of life. She was born in Connecticut and grew up fascinated by how living things functioned at their most basic levels. She earned a PhD from the prestigious Cornell University. She spent her life studying maize, the corn plant that would become the foundation for one of the most astonishing discoveries in the field.

McClintock identified "jumping genes" or transposable elements. These segments of DNA could move within a chromosome, contradicting the prevailing belief that the genome was fixed and unchanging. Her findings were dismissed as unorthodox or impossible. Still, she quietly continued her research, confident that what she was seeing was a dynamic, self-regulating genetic system.

With advancements in molecular biology, researchers began to recognize that genetic elements moved around the genome, controlling when and how traits were expressed. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983; the first woman to win the award unshared in that category.

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist. His passion for collecting, describing, and naming organisms would lead him to create the cornerstone of biological nomenclature. In 1735, he published Systema Naturae. This revolutionary work introduced the binomial nomenclature, in which each species is given a two-part Latin name, such as Homo sapiens for humans.

The system was logical and elegant, allowing scientists around the world to communicate clearly and precisely, especially at a time when linguistic and cultural barriers could regularly slow scientific advancement.

Linnaeus did more than name plants and animals; he helped create the hierarchy of kingdoms, classes, orders, genera, and species. While the details have evolved with advances in genetics and molecular biology, the foundations of biological classification have remained essentially unchanged.

Linnaeus’s classification system made it possible for scientists to organise nature systematically. His work created a shared language that later allowed Darwin, Mendel, and others to build upon each other’s discoveries. Without Linnaeus, the study of biology might have remained fragmented and regional rather than global.

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur is a biologist who made remarkable discoveries and saved millions of lives. Pasteur was born in Dole, France, and initially studied fermentation as a chemist. He was examining why wine and milk spoiled, which would lead to one of the most profound shifts in medical history: the discovery that microscopic organisms cause disease. Pasteur developed the germ theory of disease. He demonstrated that bacteria caused infection and decay, rather than spontaneous generation, which was the prevailing belief at the time. Thanks to this, hygiene, surgery, and hospital practice across Europe have improved.

He's most famous for pasteurization, which is the process that makes milk and wine safe by heating them to kill harmful bacteria without affecting flavor. He also developed vaccines for anthrax and rabies, showing that attenuated viruses could stimulate immunity.

James D. Watson

James D. Watson is the biologist who uncovered DNA's double-helix structure. Born in Chicago, Watson enjoyed birdwatching, which would spur his interest in genetics. He studied zoology and completed a PhD, joining forces with Francis Crick at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge.

In 1953, Watson and Crick proposed the double-helix model of DNA, demonstrating how genetic information is copied and passed from one generation to the next. Their discovery would transform molecular biology forever, providing the framework for how genes work, mutate, and express themselves, with applications in everything from engineering to medical diagnostics.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was a Dutch tradesman and self-taught scientist. Working from his home in Delft, he crafted the most powerful microscopes of the time, which enabled him to make astonishing discoveries. One of the most incredible of these discoveries was the single-celled organisms he observed.

Calling them "animalcules", he found a bustling universe of microscopic life within pond water, including things like bacteria and protozoa. Through meticulous letters to the Royal Society in London, he documented the world as no one had ever seen it before.

He's recognized as the Father of Microbiology despite having no formal scientific training. However, his curiosity, precision, and relentless experimentation helped him earn recognition in the field at a time when most people believed life arose spontaneously.

From Aristotle’s early observations to Doudna’s gene-editing breakthroughs, the story of biology shows how knowledge evolves through curiosity and collaboration. Each generation of scientists expands the boundaries of what we know, reminding us that discovery is a continuous conversation across centuries.

Jennifer Doudna

Jennifer Doudna has brought biology into a new era in which humanity can rewrite the genetic code. Captivated by science from a young age and encouraged by her high school teacher, she pursued a career decoding the intricate workings of RNA.

While working at the University of California, Berkeley, Doudna and her collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier invented CRISPR-Cas9. This is a revolutionary gene-editing tool that allows scientists to cut and modify DNA with more precision than ever before. For the first time in history, biologists could edit genes quickly, cheaply, and accurately.

Biology is a fascinating science. These biologists - whether they are primarily recognized as such or as some other type of scientist - even if they're more famous for their work in philosophy than in physiology, as Aristotle is - changed the world in their time and continue to impact ours. What more could you ask of any scientist - of anyone, really?

Summarize with AI: