[...] the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.

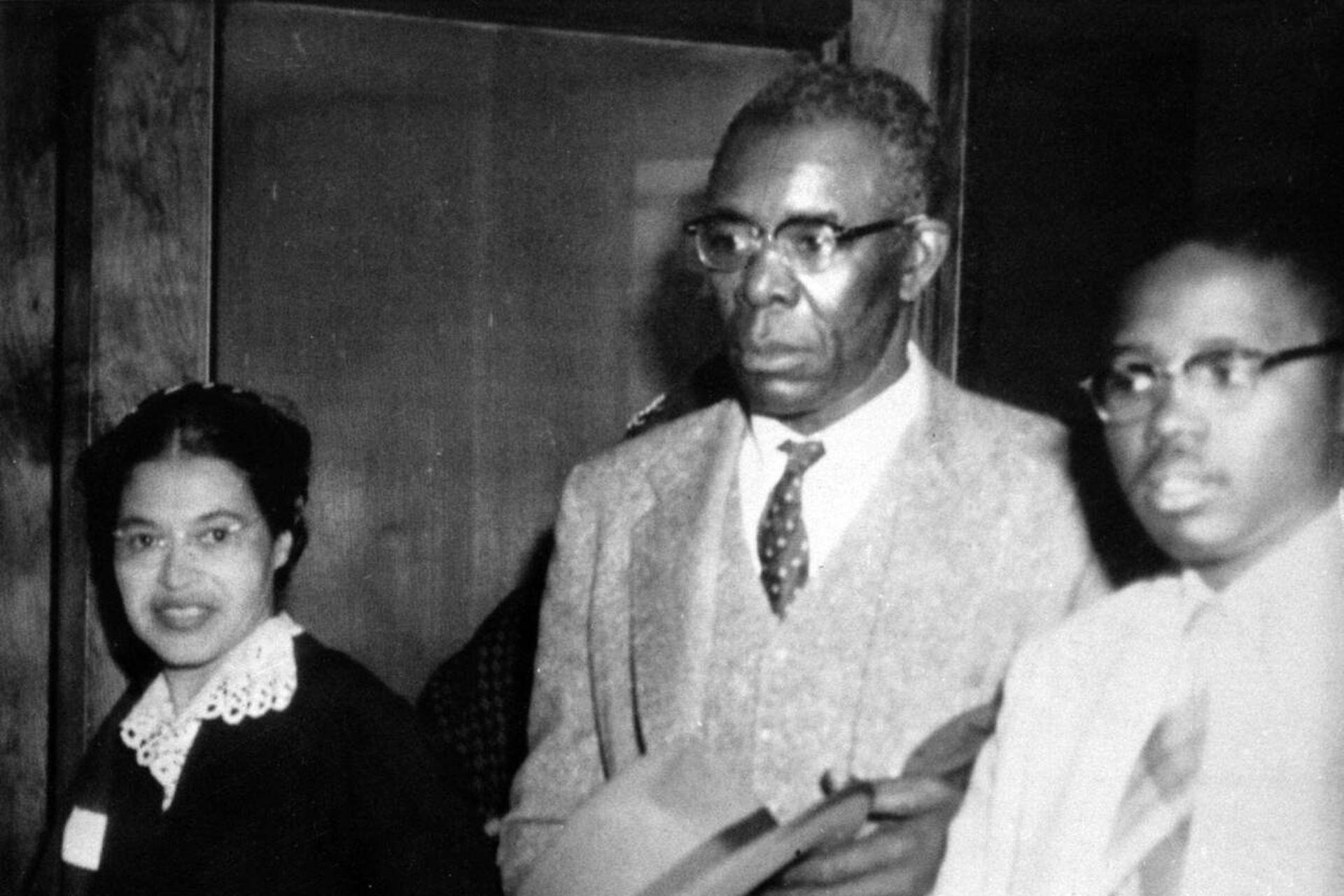

Rosa Parks

The Montgomery Bus Boycott began with a single peaceful act of resistance. It would go on to change the course of American history. When Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat, she helped spur on direct action that would last over a year and inspire movements across the country.

Background of Racial Segregation in Montgomery

Racial segregation was rampant in Montgomery in the 1960s. Transport, education, and public services were all segregated. City laws enforced separation between white and black residents, with violations resulting in arrests, fines, or violence. It was against this background of racial segregation that the fight for civil rights would take place in Montgomery, with similar situations echoed across the country.

Rosa Parks’ Act of Defiance

Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down… We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial.

Women’s Political Council leaflet, drafted by Jo Ann Robinson, Dec. 2–3, 1955

Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat on December 1, 1955. This wasn't her first act of defiance or activism, but instead the result of years of quieter activism. This may be portrayed as a spontaneous act by someone sick of racial segregation, but it was instead just one part of her history of activism, it just happened to become one of the key moments of the civil rights movement. Her arrest was the spark that helped unify Montgomery's Black community.

The Arrest on December 1, 1955

Though the arrest happened pretty quickly, the effects were felt far beyond the bus. After Parks refused to give up her seat, she stayed calm as the driver stopped the bus and called the police. She was taken into custody, fingerprinted, and charged. Her arrest became the focal point for the movement.

Immediate Community Response

News of the arrest quickly spread through the Black community in Montgomery. There was an organized response within hours as activists who'd already been preparing realized this was the turning point. Churches, local leaders, and members of the Women's Political Council quickly mobilised. Outrage turned into unified collective action.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

We are not wrong in what we are doing. If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong… And we are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

Martin Luther King Jr., Holt Street Baptist Church, December 5, 1955

The Montgomery Bus Boycott became one of the most important mass protests in American history just like the March on Washington nearly a decade later. Initially a one-day demonstration, it grew into a 381-day campaign. It responded to the national struggle for civil rights. Montgomery's Black citizens challenged segregation in the city and forced change both at the local and federal levels.

December 1, 1955

Rosa Parks Arrested

Parks refuses to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus and is arrested, catalyzing citywide action.

Night of Dec 1–2, 1955

WPC Mobilizes

Jo Ann Robinson and the Women’s Political Council produce and distribute tens of thousands of boycott leaflets overnight.

December 5, 1955

One-Day Boycott & MIA Forms

The citywide boycott is widely observed; that evening, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) is formed, and Martin Luther King Jr. is elected president.

Winter–Spring 1956

Carpools & Mass Meetings

Churches coordinate carpools and weekly meetings to sustain momentum amid arrests, intimidation, and legal pressure.

June 5, 1956

Browder v. Gayle Ruling

A federal court rules bus segregation unconstitutional.

November 13, 1956

Supreme Court Affirms

The Supreme Court upholds the ruling, clearing the path to end bus segregation.

December 20, 1956

Boycott Ends at 381 Days

Montgomery complies with the court ruling; integrated bus service begins, and the boycott formally ends.

Organization and Leadership

Churches were the primary organizing centers for the boycott, providing meeting spaces, communication networks, and volunteer structures. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) helped formalize the movement, electing Martin Luther King Jr. as its president, a key moment on his journey to becoming one of the most important civil rights leaders of the time. The boycott's successes were largely due to the movement's coordination and leadership.

maintained by church coalitions, carpools, and weekly mass meetings.

Strategies and Challenges

Maintaining a year-long boycott is no easy task. It required resilience in the face of intimidation, financial pressure, and even violent attacks. Daily bus travel was replaced by carpool systems, volunteer drivers, and community fundraising so that workers could keep their jobs while supporting the protest. Harassment, arrests, and bombings couldn't stop the movement.

of Montgomery’s bus riders were Black.

Legal Battles and Court Decisions

At the same time as the boycott, a legal strategy was unfolding in the court. The Browder v. Gayle case was filed by Black women who'd experienced discrimination. This case allowed them to challenge segregation through legal means. The combination of protest and legal action helped create a two-pronged attack that would end bus segregation.

Aftermath and Legacy

When the boycott ended, it was a turning point for Montgomery and the entire civil rights movement, proving that coordinated, nonviolent action could achieve results against segregation. Though they started as local protests, they became a national symbol of justice, with Rosa Parks becoming one of the most important female leaders of the civil rights movement. The boycott was an inspiration for other local movements and the national effort against segregation.

Desegregation of Montgomery Buses

When the Supreme Court ruling took effect on December 20, 1956, Montgomery officially ended enforced bus segregation. The next day, Black citizens could board buses and sit where they liked for the first time in decades.

Impact on the Civil Rights Movement

Empowered by the boycott's success, the civil rights movement shifted to a more nationwide effort. Martin Luther King Jr. became a prominent leader, showing the value of nonviolent direct action strategies, inspiring similar protests across the South. It also helped provide a model for community mobilisation that actions from sit-ins to Freedom Rides could use, helping build momentum that would lead to landmark federal legislation.

Summarize with AI: