By the 1860s, the shogunate concept had simply gotten too big. The daimyo, wealthy landowners with vast holdings, vied for more power against the increasingly punishing shoguns. Wars and infighting were destabilising the empire, so the daimyo allied themselves with the emperor to overthrow the shogunate. That's one reason for the shogun's downfall, but internal fractures and external pressure had major impacts, too.

An Overview of Shogun Rule

In 1868, Japan saw the end of centuries of shogun rule.

This system of military government reigned for nearly 1000 years. The emperor, the spiritual leader of the country, appointed the first shogun before the Heian Period (794 - 1185).

Establishing a firm date for the beginning of shogun rule sends historians into furious debate. The first shogun was either Tajihi no Agatamori, installed in 720, or Ōtomo no Otomaro, a general of the Nara Period (710 - 794).

However, one fact is clear: as shogunate rule took hold, three clans dominated:

The Kamakura Shogunate

- ruled from 1192 to 1333

- nine successive shoguns

The Ashikaga Shogunate

- ruled from 1338 to 1573

- 15 successive shoguns

The Tokugawa Shogunate

- ruled from 1603 to 1868

- 15 successive shoguns

In the early, uncertain days of shogun rule, the emperor likely didn't mind handing over some government duties to his top general. However, it didn't take long for the shogun to see themselves as more fit for leadership.

Especially in the early history of the shogunate, important dates were not specified.

The beginning of the Kamakura rule is alternately 1185, and 1192.

Today's historians mostly reject the earlier date. So, we cite the later date, understanding that it is not absolute.

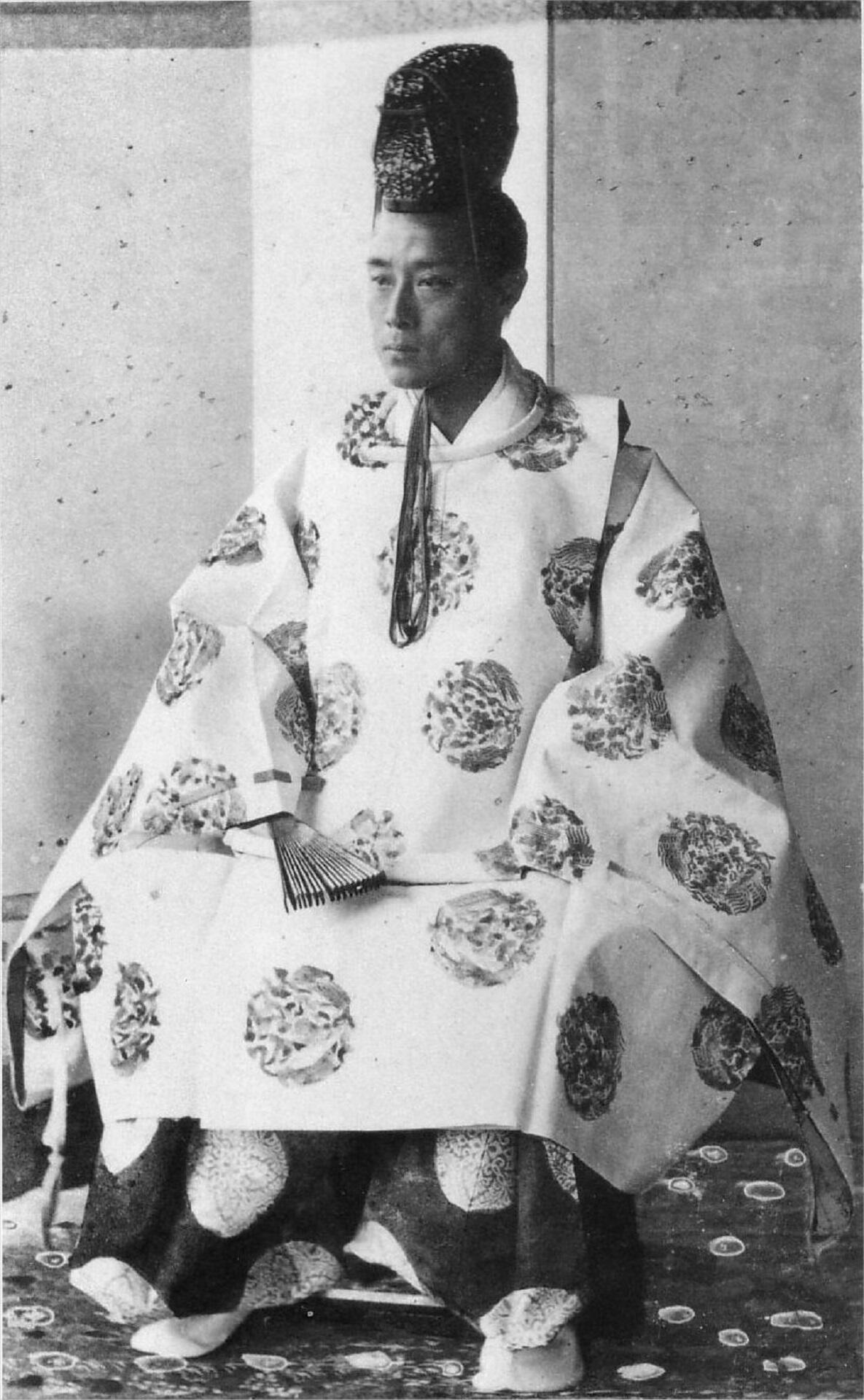

Minamoto no Yoritomo, pictured above, was a samurai of the Kamakura clan. He seized power from the emperor and nobility, installing himself as the first shogun of his clan, in 1192.

The emperor nominally appointed shoguns, but that was just a matter of ceremony. From Minamoto's time, the role became hereditary, with successive sons taking their fathers' place at the helm.

Between the Kamakura and Ashikaga shogunates, the emperor attempted to regain power.

This interlude, called the Kenmu Restoration, went from 1333 to 1336. Samurai Ashikaga Takauji helped the emperor regain some power but, in the end, the restoration failed. The emperor fled, allowing the Ashikaga clan head to install a compliant emperor, and seize control. So, shogun rule carried on.

Women During Shogun Japan

Women played a significant role under shogun rule, but their feats went largely unrecorded, except for a few remarkable instances. The Empress Jingū, who had a hand in many of Japan's pivotal events, is one example of such. So is Tomoe Gozen, one of many female samurai with legendary fighting skills.

Decline: What Caused the Fall of the Shogun?

Historians would hesitate to point to a single incident being the decisive push into shogun's decline, and rightly so. It was a collection of factors, some provoked and others natural. However, all agree that the Tokugawa shogunate led a relatively peaceful society.

They oversaw cultural and economic development. Among other initiatives, they paved roads and built markets, to make trade easier. They also standardized coinage. With all these improvements, what happened to bring about their downfall?

Natural Disasters

Japan has always suffered under nature's hand. Earthquakes and tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, cold weather and short growing cycles have long made living off the land a risky proposition. Across the era of shogun rule, we count three major famines:

The Kanki Famine

- 1229 to 1232 (est. dates)

- under Kamakura rule

The Kyōhō Famine

- 1732 to 1733

- under Tokugawa rule

The Tenmei Famine

- 1782 to 1788

- under Tokagawa rule

The results of these famines led to citizen unrest. One could never say that shogun life was always peaceful and harmonious; people had much to gripe about. Despite the Tokugawa shogunate working to build food stores, they were powerless when nature struck.

Economic Hardship

Famines aside, economic troubles were a staple of life in shogunate Japan. Peasants earned meager wages, and had to give a fair portion back in taxes. Towards the end of shogun rule, even the revered samurai weren't earning enough; they took on extra work to feed their families. Centuries of grumbling discontent exploded, helping bring about the end of shogun rule.

Isolation

The lack of trade with outsiders also caused substantial economic hardship. Furthermore, the self-imposed isolation blocked new policy ideas and initiatives from flowing in. Japan had enjoyed a population boom, but its government ruled as it had for centuries.

The shogunate was incapable of dealing with modern pressures and conditions. It lost support from the samurai, religious groups, and the noble classes. The peasant classes, long simmering in discontent, added their voices to the shogunate's opposition.

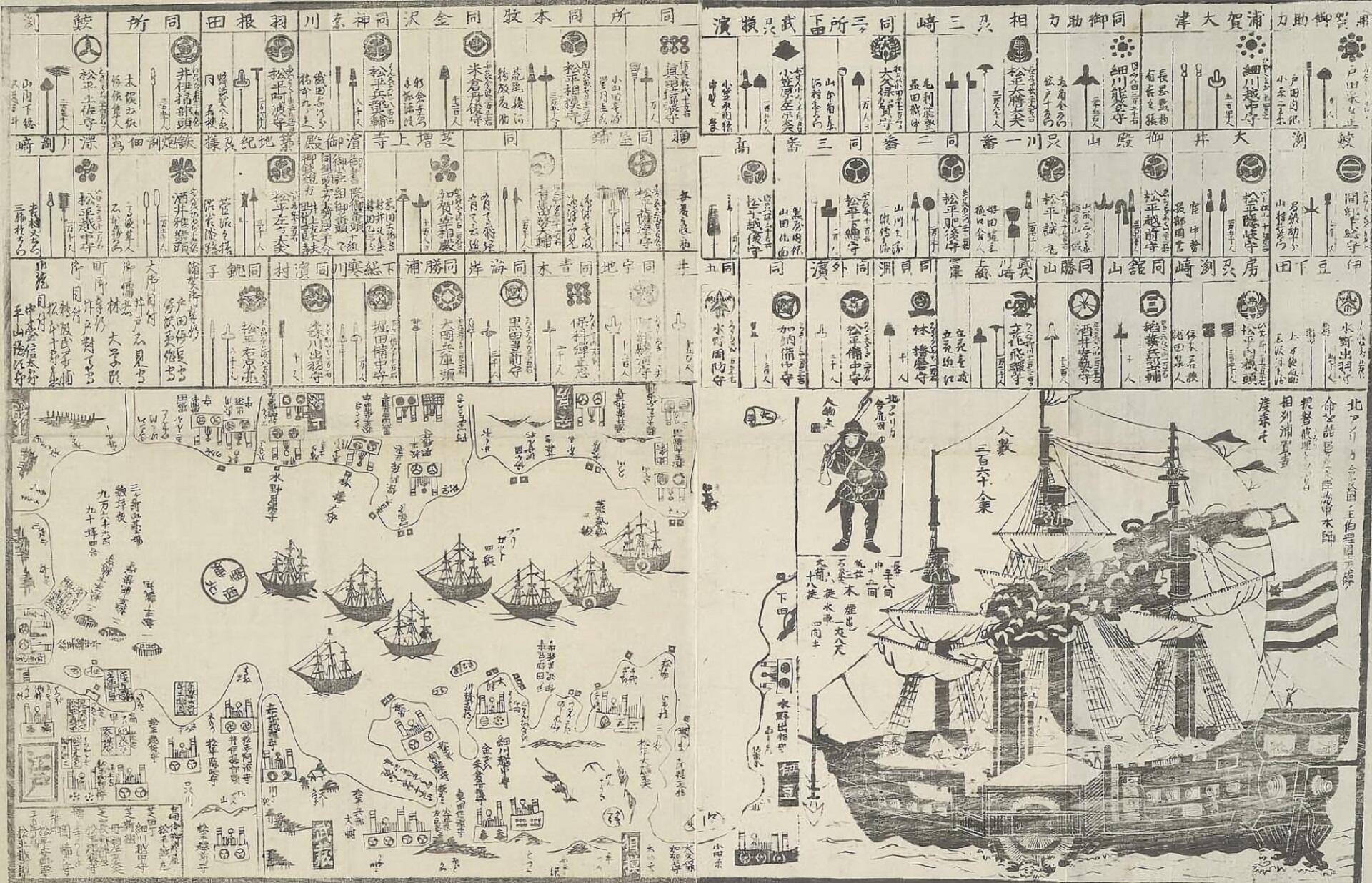

External Pressure

Just as commerce in Japan strangled under the lack of trade opportunities, foreign forces were crowding the shores to access Japanese markets. Commodore Matthew Perry battered Japan's defences, demanding access (in 1853). From then on, a series of treaties with, and concessions to outsiders weakened the shogun's power and position.

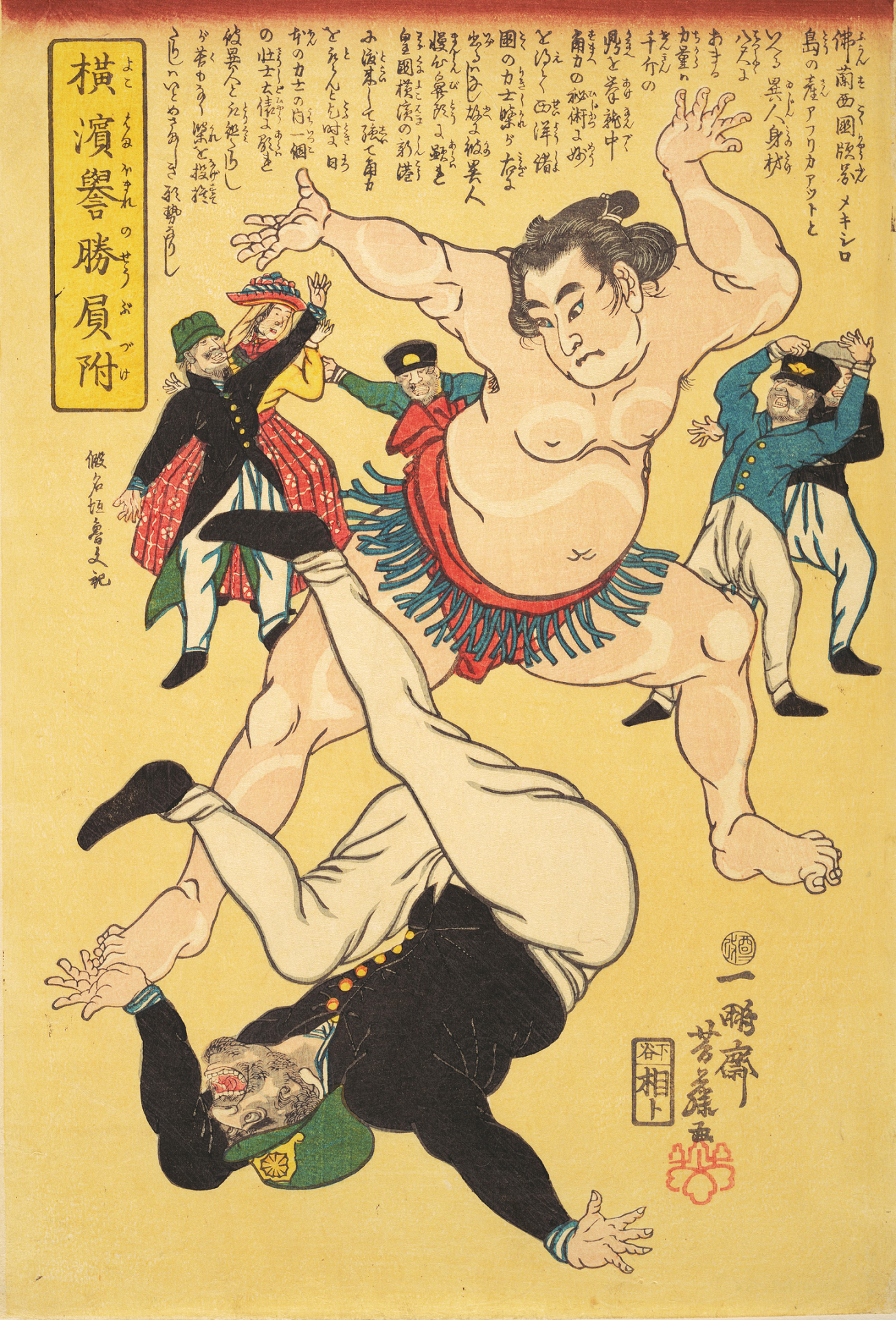

The Boshin War: the End of Shogun Japan

By the 1860s, the nobles and samurai had had enough of shogun rule. The shogunate's dealings with foreigners further provoked rage. The growing Western influence on the Japanese economy cut the Japanese people away from their own prosperity.

A group of samurai from the western provinces of Tosa, Satsuma, and Chōshū, descended on the imperial court.

With the help of court officials, they succeeded in swaying the young, inexperienced emperor to their cause.

He surrendered political power to the emperor, hoping his abdication would permit his clan a seat in the new government. The opposition had other ideas, namely banishing the House of Tokugawa. In response, the last shogun launched a military campaign to seize the Kyoto imperial court.

Imperial forces had improved weaponry and new fighting tactics. Though a smaller force, they subdued Yoshinobu's fighters. Other battles he fought, in and around Edo, were likewise unsuccessful. After the city we now call Tokyo fell, Yoshinobu surrendered.

The last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, realized how dire his situation was.

To the state historians, scribes, and warriors of feudal Japan, this clash was like all others. In many ways it was, except that it decisively ended shogun rule. Hordes of malcontents, finally exhausted from narrow leadership and their lack of political autonomy, finally seized power, ending shogun rule for good.

The Japanese Civil War

In fact, civil wars flared throughout the centuries of shogun rule. The empire was plagued with clans fighting one another for power and possessions, notably during the Sengoku period. This was an era of social upheaval that spanned the 15th and 16th Centuries. Among those conflicts, we count:

- The Kyōtoku incident (1454)

- The Ōnin War (1467-1477)

- The Meiō incident (1493)

- The Eishō delirium (1507)

- Battle of Katsuragawa (1527)

- Battle of Shari-ji (1547)

- The march on Kyoto (1568)

- The Shimabara Rebellion (1638)

Historians and interested parties posit that one such war took place between 1910 and 1912. Remote northern prefectures rebelled against the fledgling Republican government. The northerners formed the Confederacy of Japan, intending to wrest control from the existing seat of power. No record of these events exists.

Thus, the Boshin War is likely the Japanese civil war people ask about. The clashes between the Tokugawa shogunate and those wanting to return power to the imperial court lasted one year. Once the dust settled, Japan's most notable reformation began.

The Meiji Restoration

The Meiji Restoration is generally recognized as the end of the timeline for shogunate-era Japan. It restored imperial rule, with Mutsohito - Emperor Meiji, at its head. This political event took place on January 3, 1868, consolidating political power onto the emperor. Political and social structures changed dramatically, and the country began to industrialise.

Emerging from Shogun Rule: Evolving Japan

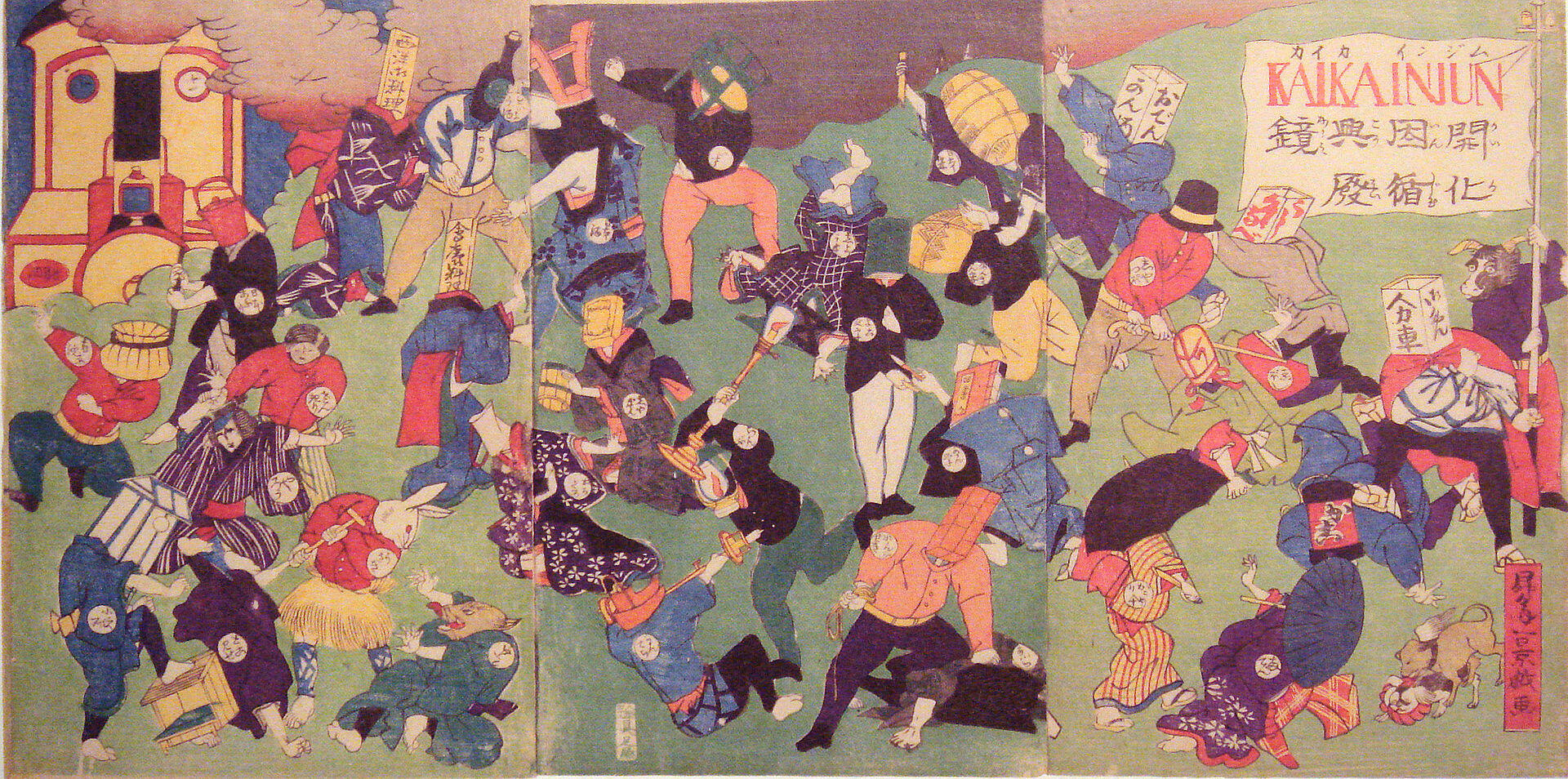

Of course, these changes did not happen overnight. Restructuring an entire country takes time, money, and political will. Many missteps led to further uprisings, and much political violence.

Western influence during this period replaced Confucianist social structures, making Japan the first Asian country to modernize along European standards. Public education, international trade, and industrial growth fueled modern Japanese life. Not everybody was on board with all the changes, as this image shows.

These initiatives' downsides included the destruction of traditional Japanese culture. Many castles were torn down or repurposed, like Hiroshima Castle, which became a military facility.

Samurai practices, from the chonmage (topknot) hairstyle to the mode of dress, were outlawed. Western styles of dress and grooming took precedence over traditional looks.

The Edo period was the Tokugawa shogunate's defining era. It was a time of contrasts, between supreme control and the unraveling of shogunate rule. Social structures - hierarchies and roles were rigid, causing many to rebel.

Economic hardship led many to rise up against their rulers, especially the peasantry. Under fire from the wealthy and the poor, the shoguns had no room left to manoeuvre. Ending shogun rule was their only option, which led to society opening up - and a whole host of new problems to solve.

Summarize with AI: