With this same key Shakespeare unlocked his heart.

William Wordsworth, from “Scorn not the Sonnet” (1827)

If you are studying poetry, Shakespeare or English literature at any level, you will inevitably have to grasp with this thing called the sonnet. Any idea what this might be? A sonnet is a 14-line poem, usually written in iambic pentameter, that follows a specific rhyme scheme and often explores themes like love, time or nature. Thanks to this article, you'll be able to identify the main features of this literary form and maybe even consider how to write your own! We hope you find it helpful!

Here are the main types of sonnets you’ll learn about:

- 📜 Petrarchan Sonnet: Also known as the Italian sonnet, with an octave and a sestet. Follows a rhyme scheme of ABBAABBA CDCDCD or ABBAABBA CDECDE.

- 🎭 Shakespearean Sonnet: The English form made famous by William Shakespeare, with three quatrains and a couplet. Follows a rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

- 🧩 Spenserian Sonnet: A variation with interlocking rhyme schemes created by Edmund Spenser. Follows a rhyme scheme of ABAB BCBC CDCD EE.

- 🖋️ Modern Sonnet: Contemporary twists on the traditional form, often bending traditional rules. This type of sonnet does not follow a rhyme scheme.

What Is a Sonnet?

For those of you who have never before set foot into the world of literature, let's start from the very basics. A sonnet is a form of poetry. This means that the word refers to a range of different poems that share certain conventions of length, structure, style, and themes. These conventions are what make a sonnet a sonnet (and don't panic, as we outline these below).

The History of the Sonnet

What is super-important to remember in the study of literature is that poetic conventions are determined by history - meaning that you need to know the history of poetic forms if you are really going to understand what the poets are doing. The sonnet is originally an Italian invention - and the word sonnet itself is derived from the Italian word “sonetto,” which means a “little song” or sound. Developed in Sicily by a guy called Giacomo da Lentini in the thirteenth century, this little poetic form (whose conventions had not yet been formalized) inspired the greatest poets of the Italian Renaissance.

These include Petrarch - about whom you'll hear much more - Dante, and Guido Cavalcanti. Due to these poets' contemporary fame and prolific work, the sonnet became with them recognizable as it is today. And, from this point, people in England and France began to write sonnets too. Over the centuries, all of Europe started to write sonnets - and, in the English speaking world, after Shakespeare, some of the greatest sonnet-writers are to be found in the Romantic period at the turn of the nineteenth century (these include names like John Keats, William Wordsworth, and Percy Bysshe Shelley). Poets are still writing sonnets today - but, these days, writers are more comfortable with playing with the once-strict structure of the form. We'll talk about this more below.

Why Do Poets Write in the Sonnet Form?

Let it be said that the form has had enduring appeal among poets for a number of reasons. Firstly, the appeal of the form is due to its association with some of the biggest names in the history of literature: Shakespeare, Petrarch, Wordsworth. As you become more familiar with poetry, you will see that poets like to refer back to the ways that other poets had written in the past; the sonnet offers a great way to do this.

Secondly, the sonnet, given its brief length, is great for expressing a feeling, thought, or idea. The brevity facilitates the communication of a strength of feeling that can be lost in longer forms.

Thirdly, whilst the sonnet is traditionally known for focusing its attentions on the theme of love, the form allows for a great flexibility in its content. You will these days see sonnets written on everything from politics to war to ice cream. What makes this possible is the form's argumentative structure, which, as you will see below, is an essential part of the sonnet.

The Main Types of Sonnet and their Rhyme Scheme

What are the different sonnet types? In the English-speaking world, we usually refer to three discrete types of sonnet: the Italian (also known as the Petrarchan), the English Sonnet (also known as the Shakespearean Sonnet), and the Spenserian. All of these maintain the features outlined above, fourteen lines, a volta, iambic pentameter and they all three are written in sequences. The primary difference is the different sonnet rhyme schemes. We'll look at these three types of sonnet, and then finally consider some of those that don't really fit into the structure we have all been taught.

The Italian Sonnet (also known as the Petrarchan Sonnet), the English Sonnet (also known as the Shakespearean Sonnet), and the Spenserian Sonnet.

Petrarchan Sonnet

The first sonnet is the Petrarchan, or Italian, sonnet. Named after one of the form's greatest practitioners, the Italian poet Petrarch, the Petrarchan sonnet was the earliest strict sonnet form (he lived from 1304 to 1374). As we noted above, the Petrarchan sonnet is divided into two stanzas: the octave (the first eight lines) followed by the answering sestet (the final six lines). Let's take a look at a Petrarchan sonnet, by the English poet William Wordsworth (as this is easier than reading medieval Italian!).

London, 1802

(A) Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

(B) England hath need of thee: she is a fen

(B) Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

(A) Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

(A) Have forfeited their ancient English dower

(B) Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

(B) Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

(A) And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

(C) Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart:

(D) Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

(D) Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

(E) So didst thou travel on life's common way,

(C) In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

(E) The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

So, here, in the first line, we've added markings to highlight the stress of the iambic pentameter (try it for yourself in the rest of the lines!). And we've neatly highlighted the volta after the eighth line (do you see how the poem's tone changes - from a critique of England to a celebration of Milton?).

In Petrarch, the volta usually separates the shift from an argument or question in the octave to a resolution in the sestet.

But what do those letters mean before each line? This is how we refer to rhyme scheme, in which A rhymes with A, B with B, and where each new sound requires a new letter. So, what do we have here? ABBAABBA, CDDECE. The Petrarchan sonnet will almost always begin with that ABBAABBA octave. However, the rhyme scheme of the sestet can change - so watch out. Here, Wordsworth uses CDDECE, but the most common rhyme schemes in Petrarch are CDECDE or CDCDCD.

After the Petrarchan sonnet was first brought to England by Sir Thomas Wyatt, Henry Howard began translating and writing his own versions of Petrarch. His works were considered more faithful to the original than the work of his English counterparts. He made modifications to the Petrarchan sonnet which then became the structure of what we know as the Shakespearean sonnet. This structure was established to better suit the English language which was somewhat lacking in the rhyming words that Italian boasts.

Have you ever heard of Limericks light-hearted poems?

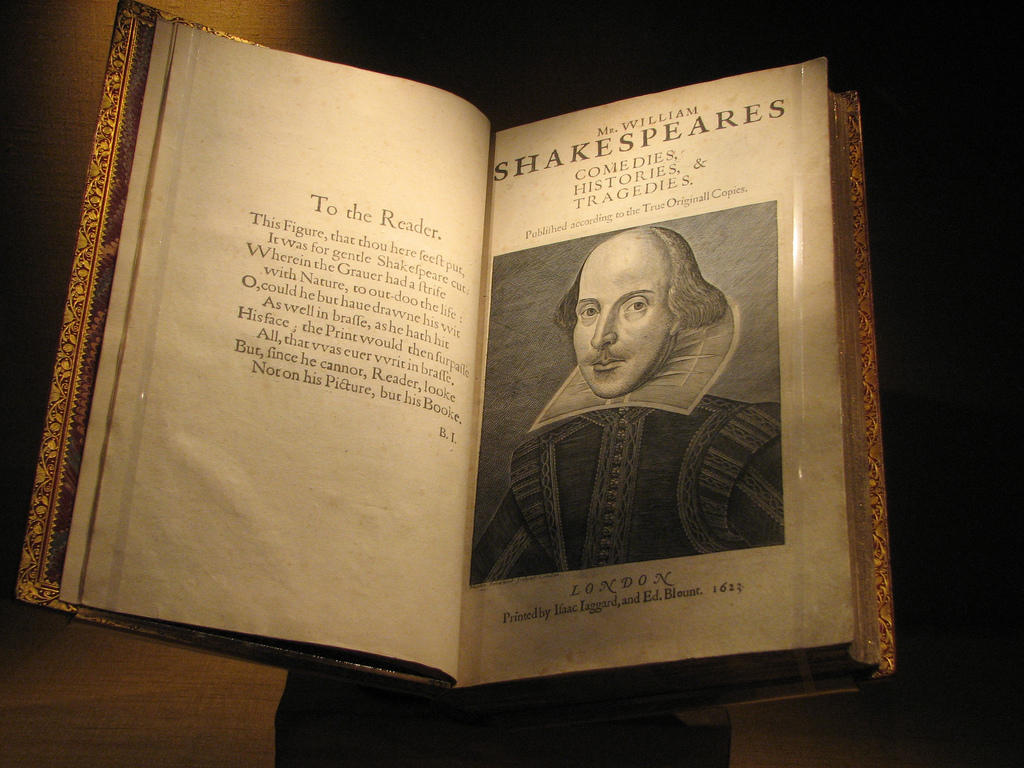

The Shakespearean Sonnet

The Shakespearean, or English sonnet, follows a different set of rules. Here, there are usually three quatrains and a couplet following a rhyme scheme like this: ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG. This is the primary difference between the Petrarchan and the Shakespearean sonnet. Let's take a look at Shakespeare's Sonnet 130:

(A) My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

(B) Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

(A) If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

(B) If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

(C) I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

(D) But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

(C) And in some perfumes is there more delight

(D) Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

(E) I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

(F) That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

(E) I grant I never saw a goddess go,

(F) My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

(G) And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

(G) As any she belied with false compare.

Much like in the Petrarchan sonnet, the Shakespearean sonnet contains a volta. There is a difference here, however. The volta can either come after the first eight lines or, as in Sonnet 130, at the beginning of the couplet. Here, it is used to signal a conclusion, explanation, or counterargument to the previous 3 stanzas. In Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 the first twelve lines focus on the speaker’s mistress, comparing her unfavourably to nature. But the final couplet changes the tone completely, that despite all of her flaws he does love her. Shakespeare uses Sonnet 130 as a satire of other poets who compare their loves to nature’s beauty. In fact he takes it to the extreme nearly leaving the mistress completely unlovable!

What is the difference on the and the? Here is a great informative video on YouTube!

You can also read on Japanese Haiku poetry in this article!

The Spenserian Sonnet

A contemporary of Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser lived from 1552 to 1559. His sequence, Amoretti, was his main engagement with the sonnet form - and his other works included The Faerie Queene, an allegory about Elizabeth I, and The Shepherd's Calendar, a poem about shepherds, surprise surprise. The Spenserian sonnet has a similar structure to a Shakespearean one, with three quatrains followed by a couplet. The interesting thing about the Spenserian sonnet is, of course, the rhyme scheme. Let's take a look at Spenser's Sonnet 75.

(A) One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

(B) But came the waves and washed it away:

(A) Again I write it with a second hand,

(B) But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

(B) Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay,

(C) A mortal thing so to immortalize,

(B) For I myself shall like to this decay,

(C) And eek my name be wiped out likewise.

(C) Not so, (quod I) let baser things devise

(D) To die in dust, but you shall live by fame:

(C) My verse, your virtues rare shall eternize,

(D) And in the heavens write your glorious name.

(E) Where whenas death shall all the world subdue,

(E) Our love shall live, and later life renew.

So, what do we have here? Remembering that Shakespearean sonnets follow the ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG form, the Spenserian sonnets are slightly different: ABAB, BCBC, CDCD, EE. So, the second rhyme of the first quatrain is taken to be the first of the second quatrain. Again, it ends with a couplet. Where's the volta? Look at line nine, the first line of the final sestet. 'Not so', says Spenser, introducing a contradiction. As in Shakespeare, the volta either appears here or at the beginning of the final couplet.

The Main Types of Sonnet

| Type | Rhyme Scheme | Volta Position |

|---|---|---|

| Petrarchan | ABBAABBA; CDECDE or CDCDCD | After first octave. |

| Shakespearean | ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG | After first octave or beginning of final couplet. |

| Spenserian | ABAB, BCBC, CDCD, EE | After first octave or beginning of final couplet. |

Which are your favorite types of sonnet rhyme scheme? Also, have you ever heard of an Epic style poem?

The Most Important Features of a Sonnet

As we saw above, a sonnet is simply a poem written in a specific form. But to recognize a sonnet when you see one, you need to know the specific characteristics of that form. So, to summarize, here are the need-to-know features of a sonnet.

The Sonnet's Main Features

| Fourteen lines | Generally, all sonnets have fourteen lines. You will find some exceptions, but the poets will do this deliberately. |

|---|---|

| Volta | The fourteen lines are divided into two sections, usually of eight lines and six. The break between the two parts is known as the volta. |

| Iambic pentameter | This is what we call the metre of the poem: the number of syllables in each line of the poem. An 'iamb' is a set of two syllables, the first unstressed and the second stressed. 'Pentameter' shows that there are five of these 'iambs' in a line. So, you have ten syllables: unstressed, stressed; unstressed, stressed, etc. |

| Rhyme scheme | Different types of sonnets have different rhyme schemes, and some don't rhyme at all! You'll see more about this below. |

So, to flesh this about a bit, let's pay a bit more attention to each feature.

Lines and Structure

We've just noted that a sonnet has fourteen lines. But what you need to remember is that depending on the type of sonnet, these lines are arranged in different ways. So, in a Petrarchan sonnet (we told you he'd come up again!), the lines are grouped into two: an octave (that means a group of eight lines) and a sestet (a group of six). In Shakespearean sonnets and Spenserian sonnets, on the other hand, you have three quatrains (four lines) and a couplet (two lines). You'll find more on how these lines rhyme in the sections on each type of sonnet below.

The Volta

Whilst you will find a volta in many other forms of poetry, they are really quite important to the sonnet. What do we mean by the volta, then? In Italian, this word means 'turn' - and, in the sonnet, this is the moment at which a change occurs in the poem. This change might be in tone, argument, or thematic focus - but it is very rare to find a sonnet without one. As we note above, these usually occur after the eighth line of the poem - for Petrarch, after the octave, whilst for Shakespeare and Spenser after the second quatrain. You'll notice this change quite easily, as they are usually signaled with a 'but', 'however', or 'and'.

Iambic Pentameter

This may look like a scary poetry word, but don't worry about it too much. Let's break it down. 'Metre' refers to the rhythmic structure of a line in poetry: how many syllables, how these are grouped together. 'Penta-' comes from the Greek word for 'five'. So, from 'pentameter' you know that the metre of a sonnet has something to do with five.

As we said above, the word 'iamb' refers to a group of two syllables, one unstressed and one stressed. There are five of these in each line when we talk about iambic pentameter. As all English literature teachers will tell you, the line will scan like this: dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH dee-DAH. To see this in action, look at this line from Shakespeare's famous Sonnet 18, in which we have highlighted the stressed syllables:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Count the syllables in the line (there are ten!). Now, count the stressed syllables (there are five!). However, if we switch the stressed syllables with the unstressed ones, we can see how the line becomes a little clumsy:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

The Sonnet Series

One of the main historical conventions of the sonnet is that they usually come in series. Think about Shakespeare's poem above. Why is it called 'Sonnet 18'? He didn't name it that. Rather, because he wrote 154 sonnets, each individual one is known by its number. A lot of people have written sonnets in sequences. The most famous early sonneteers all wrote series: Philip Sidney's Astrophil and Stella; Shakespeare's Sonnets; Spenser's Amoretti.

This convention has remained with us, as, in the twentieth century many other writers have composed sonnet sequences: Rainer Maria Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus, John Berryman's Sonnets. These are the things that have developed the association of sonnets with the theme of love - as all of these sequences deal with a passionate speaker talking to a loved object.

Do you know what Ballad poetry style is?

Playing with the Form: Other Sonneteers

Whilst what we have just covered are the main historical types of sonnets, lots of poets have decided to take the basic structure of the form and change its content. Consequently, whilst these above are important to know, it is worth stressing that they are not the only forms of sonnets around. Let's take a look at just a handful of different sonnets that play with the conventions of the form.

Carol Ann Duffy's Anne Hathaway

A poem which, if you are studying literature, you will may encounter is Carol Ann Duffy's Anne Hathaway. Take a read and see what she does with the sonnet form.

The bed we loved in was a spinning world

of forests, castles, torchlight, cliff-tops, seas

where he would dive for pearls. My lover’s words

were shooting stars which fell to earth as kisses

on these lips; my body now a softer rhyme

to his, now echo, assonance; his touch

a verb dancing in the centre of a noun.

Some nights I dreamed he’d written me, the bed

a page beneath his writer’s hands. Romance

and drama played by touch, by scent, by taste.

In the other bed, the best, our guests dozed on,

dribbling their prose. My living laughing love –

I hold him in the casket of my widow’s head

as he held me upon that next best bed.

So, what's important here? What is one of those key features of the sonnet that is missing here? You should have noticed: it is the rhyme scheme! Does the poem rhyme? Only in the final two lines. Other than that, the iambic pentameter is still there, as well as the volta.

Are you curious to listen to free verse poetry style?

Elizabeth Bishop's Sonnet

Caught -- the bubble

in the spirit level,

a creature divided;

and the compass needle

wobbling and wavering,

undecided.

Freed -- the broken

thermometer's mercury

running away;

and the rainbow-bird

from the narrow bevel

of the empty mirror,

flying wherever

it feels like, gay!

Now, how is this a sonnet? Is it a sonnet, and why? The poet, Bishop, clearly intends it to be so, entitling the poem the way she does. What do you think?

E.E. Cummings

here's to opening and upward,to leaf and to sap

and to your(in my arms flowering so new)

self whose eyes smell of the sound of rain

and here's to silent certainly mountains;and to

a disappearing poet of always,snow

and to morning;and to morning's beautiful friend

twilight(and a first dream called ocean)and

let must or if be damned with whomever's afraid

down with ought with because with every brain

which thinks it thinks, nor dares to feel(but up

with joy;and up with laughing and drunkenness)

here's to one undiscoverable guess

of whose mad skill each world of blood is made

(whose fatal songs are moving in the moon

Besides the lack of capital letters and spaces (all of which are intentional), E.E. Cummings is known for his experiments with poetic forms. Can you recognize what he has done here to the form of the sonnet? Are you looking to visit a slam poetry show?

Find Out More About Different Poetic Forms

The benefit of poetry is that there are lots of different styles once you have tried sonnets poems. Sonnets may be centuries old, but they’re still alive and well. They shape how we express love, beauty and even everyday thoughts in just 14 lines. From Shakespeare’s timeless verses to modern twists that break all the rules, the sonnet is proof that structure doesn’t limit creativity, but inspires it.

If you're feeling curious about writing your own or just want help wrapping your head around the different forms, you don’t have to figure it out alone! Superprof has amazing poetry tutors across the US who love what they do and genuinely want to share that passion with you. Whether you’re studying for school, preparing for exams or want to get into poetry, there's a tutor out there ready to help you grow at your own pace. With the right guidance, learning about sonnets can be not just easier, but fun and maybe even inspiring enough to write your own!

Summarize with AI:

This is a really helpful article! There are so many versions of people describing sonnets on the internet. This one was the most thorough and clear. Thanks for your hard work putting it together!

Thank you for the wonderful feedback! We’re glad you enjoyed the article 😄