Kami are the divine spirits of Japan's native religion, Shinto. According to Japanese folktales, there are 8 Million kami, a number considered synonymous with eternity in Japanese traditions and culture. You will encounter various monuments devoted to several gods of ancient Japanese mythology throughout Japan.

There are only 65 main Japanese gods, but there are roughly eight million kami in Japanese mythology.

Kami, or Japanese gods, can be good or evil. Throughout Japanese mythology, you will find gods that are unbelievably powerful or comparatively gentle. Today, we have rounded up a list of the most important Shinto and Buddhist Kami in Japanese myths. Read on as we elaborate on the role of these gods and goddesses.

| Kami/Deity | Role/Domain | Key Traits | Famous Shrine/Legend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raijin | God of lightning, thunder, and storms | Portrayed with hammers and drums, feared for causing storms | Guardians at temple entrances, symbolizing protection |

| Fujin | God of wind | Depicted with a wind pouch, representing the cardinal directions | Partner of Raijin, associated with storm damage |

| Inari | God of rice, prosperity, and industry | Revered for protecting rice cultivation, symbolized by fox messengers | Inari Shrine, offerings include aburaage (fried tofu) for foxes |

| Benzaiten | Goddess of love, music, and water | Associated with flowing elements like emotions, water and music | Enoshima Shrine, popular for couples to post pink ema for love |

| Tenjin | God of literature, education, and scholarship | Once a human scholar, Sugawara-no-Michizane, revered posthumously | Shrines visited by students for blessings before exams |

| Hachiman | God of military arts and war | Protector of warriors, defender of Japanese islands | Shrines across Japan honor him as a guardian |

| Amaterasu | Sun goddess and central Shinto deity | Ancestor of Japanese emperors, governs the universe and High Plains | Major influence in Shinto, symbolizing imperial legitimacy |

| Izanagi and Izanami | Creator gods of Japan | Stirred the oceans to create Japan; parents to many kami | Their story explains the origin of life and death |

| Jizo | Protector of children and the deceased | Helps children cross the Sanzu River in the afterlife | Statues adorned with bibs and hats, symbolizing guardianship |

| Ungyo and Agyo | Guardians of Buddhist temples | Ungyo symbolizes power and strength; Agyo embodies violence and aggression | Statues placed at temple gates to protect sacred spaces |

| Kannon | Goddess of mercy and compassion | Delays Buddhahood to help others achieve enlightenment | Kannon statues disguised as the Virgin Mary during Christianity bans |

| Shitenno | Four guardian deities in Buddhism | Associated with seasons, directions, elements and virtues | Protect Buddhist temples, depicted stomping on evil spirits |

| Susanoo | God of storms and the sea | Slayed the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi, symbolizing heroism | Important in Shinto creation myths, associated with courage |

| Tsukuyomi | Moon god | Represents the calm and mystery of the night | Brother of Amaterasu, highlighting balance in nature |

| Ebisu | God of prosperity and fishermen | Depicted with a fishing rod and large fish, symbolizing abundance | Popular with tradespeople and farmers |

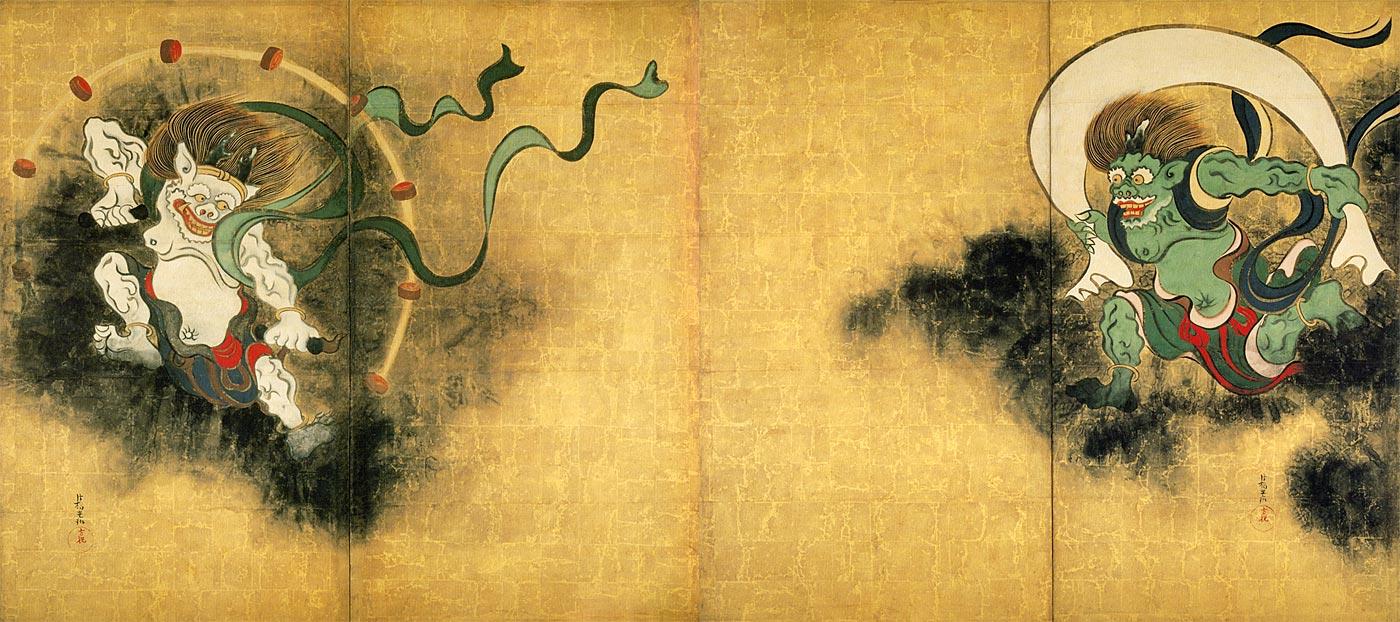

Raijin and Fujin

Raijin is a kami of lightning, storms, and thunder, who is portrayed holding hammers and surrounded by drums, whereas, Fujin is a god of wind pictured with a pouch of wind.

Together, Raijin and Fujin are the deities of weather and storms and often appear as a team.

In Japanese stories, they are the most feared kami because of the damage storms and typhoons have caused to Japanese islands throughout the centuries. As a playful anecdote, parents in Japan would tell their kids to hide their bellybuttons during storms so Raijin wouldn't consume their bellies.

As frightening deities, Raijin & Fujin often appear at the entrances of shrines and monuments as guardians. Every visitor is subject to their watchful gaze before entering. Raijin has three fingers, each denoting the present, past, and future, while Fujin has four fingers representing north, south, east, and west (cardinal directions).

Inari

Inari is a Shinto deity of prosperity, agriculture, finance, and industry. This god has approximately 40,000 shrines devoted to it, making up one-third of all shrines in Japan. It is right to say this kami is among the most revered Shinto deities.

According to Japanese folktales, Inari was very passionate about foxes and even used them to deliver earthly messages. You will often see the statues of foxes around the shrines of Inari-Okami. While visiting the shrines of Inari, people offer aburaage, Japanese food, to these foxes.

Benzaiten

Benzaiten or Benten is the Shinto god borrowed from the Buddhist belief. She is among the seven lucky kami of Japan and has many similarities with the Hindu deity, Saraswati.

Benzaiten is a goddess of everything that flows, such as water, emotion, knowledge, and music. In the common fantasy, she is a goddess of love as well. Her shrines are usually considered romantic spots for Japanese couples. Moreover, Benzaiten's Enoshima shrine is one of the most famous shrines of Japan. It is usual for couples to visit and hang pink ema or ring love bells together.

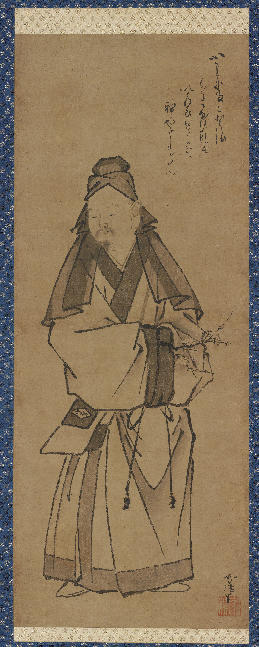

Tenjin

Tenjin is the kami of literature, scholarship, and education. Surprisingly, this kami was once a common man known as Sugawara-no-Michizane. He was a prominent poet, politician, and scholar of 8th century Japan.

Michizane was one of the Heian Court's high-ranking members, with enemies in the Fujiwara clan — the most influential family at that time. This clan was notorious for going up against the Japanese government during the Hein period.

Eventually, Michizane was banished from the Court under the clan's pressure, and shortly after that died a solitary death.

After his sudden demise, Kyoto was hit by a series of horrific floods and lightning. Many of the Michizane's adversaries, including the Emperor's sons, died in strange accidents one after another.

Meanwhile, drought and plague also spread across Japan. The government and the citizens attributed these unexpected, dreadful events to the vengeful spirit of the late Sugawara-no-Michizane.

To appease his spirit, the government subsequently reinstated his status and rank while removing all evidence of his punishment. However, chaos ensued.

In a last-ditch effort, the government bestowed his spirit with the title of "Scholarship Kami" and Tenjin (Sky deity).

They also proceeded to build a shrine explicitly devoted to Sugawara-no-Michizane. In modern-day Japan, students visit the shrine before exams for the blessings of the scholar deity!

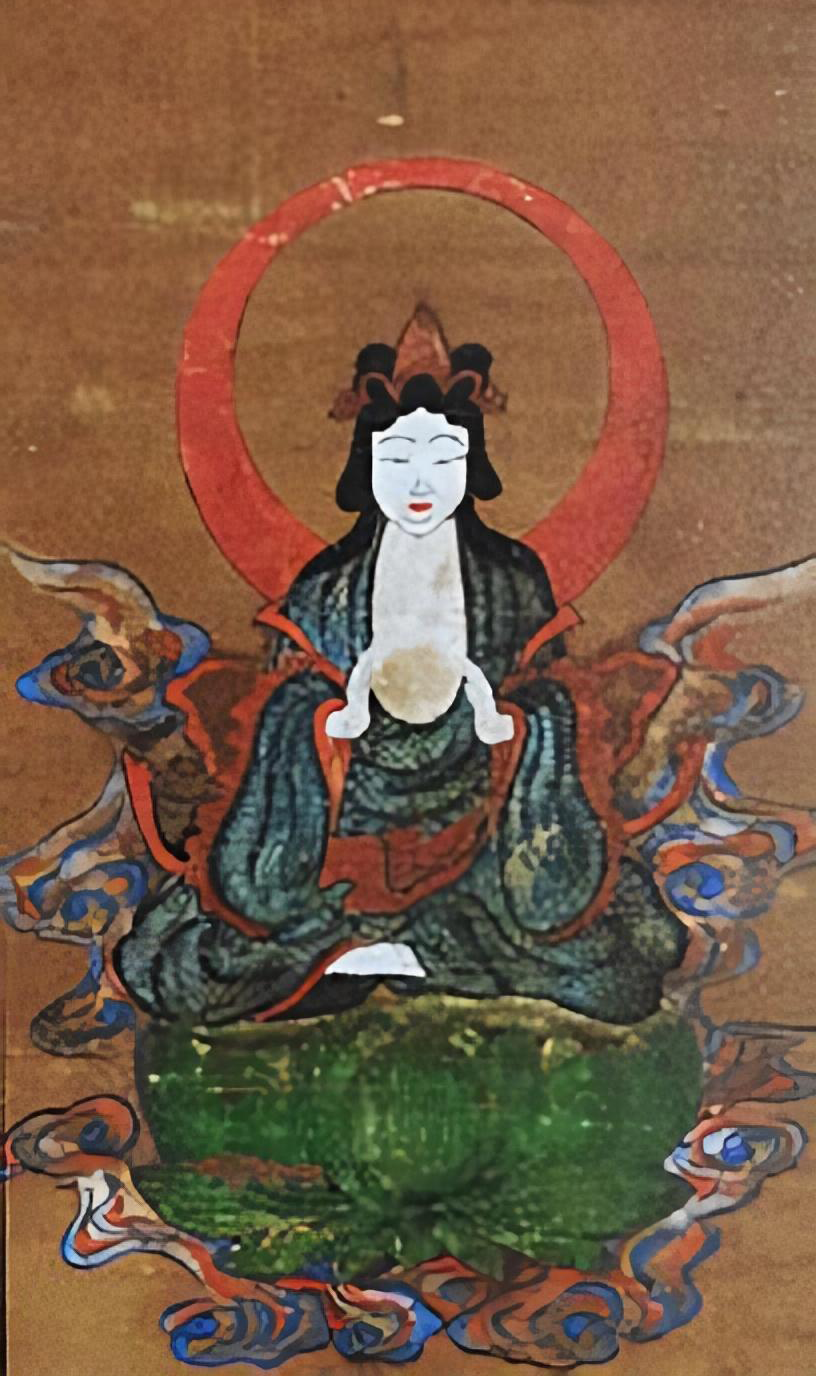

Amaterasu

Amaterasu-Omikami stewards the sun, universe, and High-Plains, from which every other kami descends. She is one of the most important deities and a primary kami in the Shinto religion.

Legend has it that most Japanese Emperors were her descendants; this was used as a rationale to defend their uninterrupted reign. Amaterasu-Omikami is the beloved daughter of Izanagi and Izanami and was born from her father's left eye. She has two other brothers named Tsukuyomi and Susanoo, both of whom are immensely powerful Kamis.

Hachiman

Hachiman is a kami of military arts and war. He is known to provide thorough guidance to warriors who wish to excel in battle, embodying the virtues of strength and strategy.

In Japanese myths, it is believed that Hachiman is the defender of all Japanese islands. He is attributed to blowing a divine wind, or kamikaze, that destroyed the large Mongol fleets of Kublai Khan, protecting Japan from invasion and earning reverence as a protector deity.

Around 25,000 shrines are devoted to Hachiman across Japan, just behind Inari, which has almost 40,000 shrines. Hachiman is also revered as the guardian of peasants and fishermen, extending his blessings beyond warriors.

His association with Emperor Ōjin further solidified his status as a powerful figure in Japanese spiritual culture.

Hachiman's influence bridges Shinto and Buddhism, highlighting his role as a deity venerated in diverse traditions, symbolizing harmony, resilience, and divine protection for the nation.

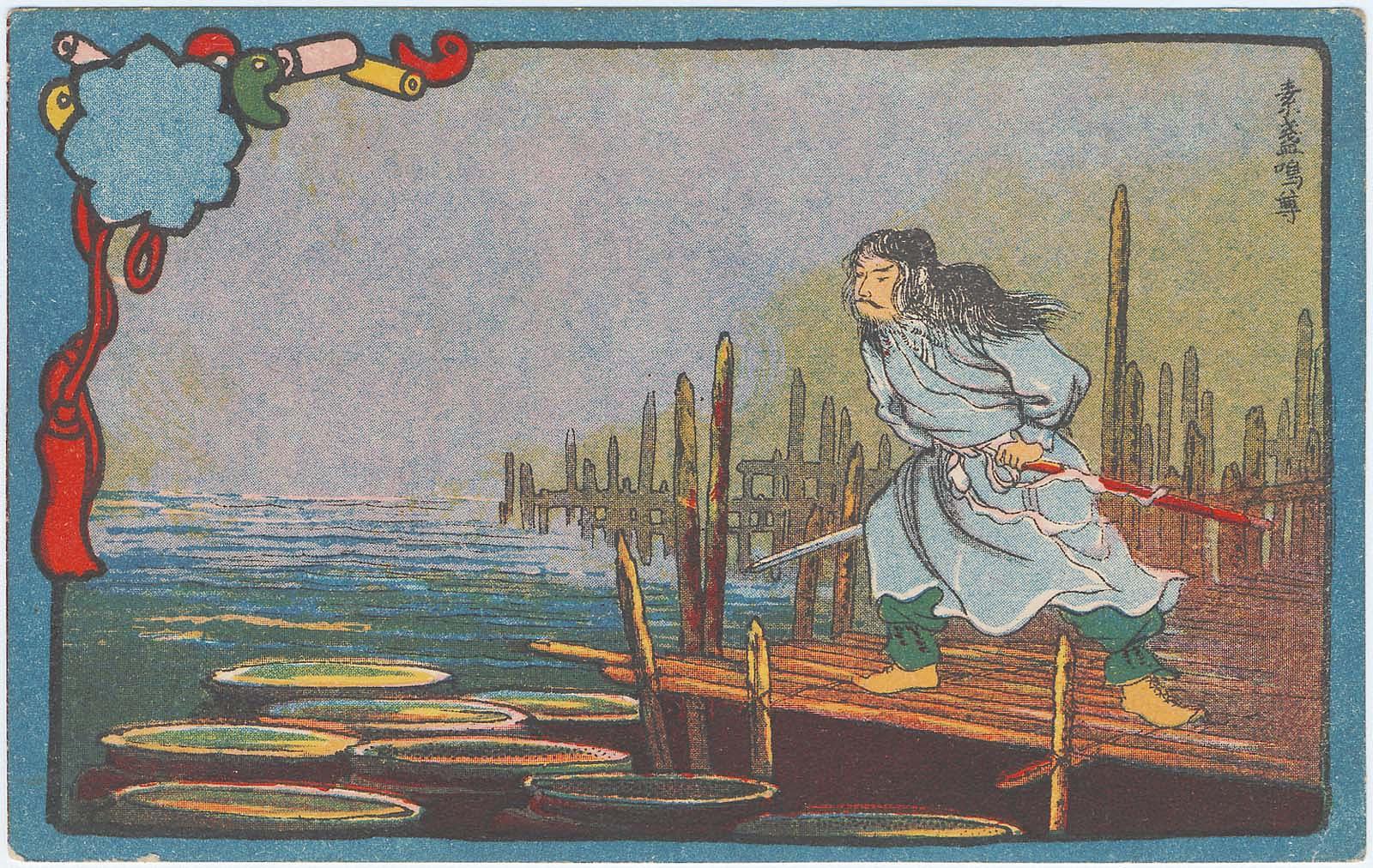

Izanagi And Izanami

Izanagi and Izanami are two of the principal deities in the creation myth of the Shinto religion.

According to the Japanese folktales, these two deities stirred the oceans with their spear. The mud that dripped from the spear's tip created Japan.

They both had hundreds of children who later on became Japanese gods and goddesses in the Shinto religion.

Among their offspring were prominent deities like Amaterasu, the sun goddess, and Susanoo, the storm god, who play vital roles in Japanese mythology. Their stories represent themes of creation, life, and death.

Jizo

According to mythical Japanese stories, it is believed that kids who pass away before their parents can't pass the divine Sanzu River in the next life as they haven't collected adequate good deeds.

They are destined to stack small stones along the riverbank for eternity. Jizo is a protector of childbirth and children. He has to help these kids cross the divine river by covering them in his robe.

Throughout Japan, you'll find temples filled with tributes to Jizo. These are mostly donated by grieving parents who lost their children.

Moreover, visitors also offer hats and bibs to stay warm. Parents would leave rocks/stones and toys near the statues hoping that their kids are guarded in the next world.

Ungyo and Agyo

Ungyo and Agyo are fearsome protectors of Buddha, often placed at entrance doors of Japanese temples, symbolizing the duality of life and death, as well as beginnings and endings. Ungyo represents power and quiet strength, with his closed mouth symbolizing contemplation and composure.

His empty hands reflect confidence in his inner power, embodying latent energy.

In contrast, Agyo signifies open aggression and outward force, with his wide-open mouth expressing the primal sound "Ah," representing creation and beginnings.

His clenched fists or weapons indicate readiness to confront evil. Together, they ward off negativity and protect sacred spaces, uniting serenity and action.

Kannon

Kannon, the Japanese Buddhist kami of mercy, is celebrated as a symbol of compassion and hope. Often depicted with multiple arms or heads, she embodies her ability to assist countless beings simultaneously, addressing diverse forms of suffering.

Her name, derived from "Kanzeon" (observing the sounds of the world), reflects her mission to listen to the cries of those in distress and offer relief.

In addition to being venerated in Buddhist temples, Kannon holds a unique place in Japanese culture.

Her image is associated with healing, protection, and guidance, making her a beacon of spiritual comfort.

The Maria Kannon statues, created during the persecution of Christians in the 17th century, represent not only the ingenuity of hidden Christians but also the universality of Kannon's merciful nature.

Her enduring legacy continues to inspire devotion, transcending religious boundaries and symbolizing the universal power of compassion.

Shitenno

Shitenno are four horrifying deities borrowed from Hindu gods to guard the temples of the Japanese Buddhists. Each Shitenno deity is linked with a season, direction, element, and virtue. In many instances, Shitenno are shown stomping on evil spirits.

Susanoo-no-Mikoto

Susanoo is the Shinto storm god and younger brother of Amaterasu. Known for his chaotic nature, he is famous for slaying the serpent Yamata no Orochi, a feat that made him one of Japan’s most celebrated mythological figures.

Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto

Tsukuyomi, the moon god in Japanese mythology, is one of the three noble siblings born from Izanagi during his purification rituals, alongside Amaterasu, the sun goddess, and Susanoo, the storm god.

Tsukuyomi governs the night and is often associated with calmness, balance, and serenity, contrasting with Amaterasu's radiant energy and Susanoo's chaotic nature.

Despite his tranquil demeanor, Tsukuyomi’s actions led to a significant rift with his sister Amaterasu.

According to legend, he killed Uke Mochi, the food goddess, after being offended by her methods of producing food.

This act enraged Amaterasu, causing her to sever ties with him and retreat, separating day from night.

Tsukuyomi is rarely depicted as a central figure in Japanese worship compared to his siblings, yet his presence as a symbol of the moon embodies the cyclical harmony of nature. His calm yet distant nature reflects the quiet mystery of the night.

Ebisu

Ebisu is one of the Seven Lucky Gods, revered as the patron of fishermen, tradespeople, and wealth. He is typically depicted with a cheerful smile, holding a fishing rod in one hand and a sea bream (tai) in the other, symbolizing prosperity, abundance, and good fortune.

Ebisu's origins trace back to Japanese folklore, where he is believed to be the son of Izanagi and Izanami or sometimes identified with Hiruko, a child born without bones but later transformed into a strong, benevolent deity.

His association with the sea makes him a favorite among fishermen, who pray for bountiful catches and safety at sea. Merchants and traders also venerate him for success in business ventures.

Shrines dedicated to Ebisu are scattered across Japan, and his joyful image represents the rewards of hard work and resilience, embodying the spirit of perseverance and the blessings of nature.

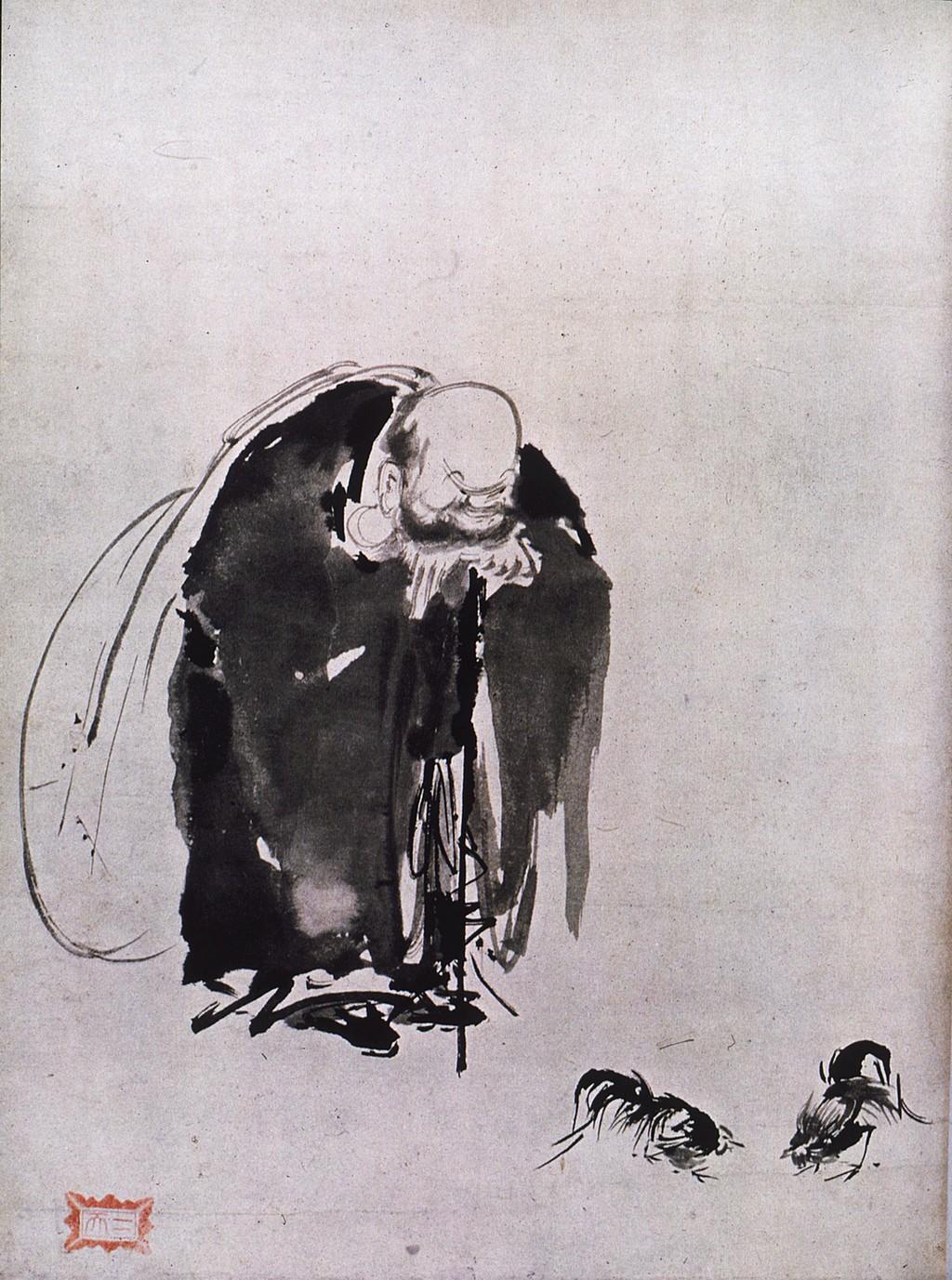

Hotei

Hotei is the Laughing Buddha and another of the Seven Lucky Gods. He symbolizes happiness, abundance and contentment, often portrayed with a large belly and a bag of treasures.

Known for his cheerful demeanor, Hotei is a patron of children, fortune, and happiness, spreading joy and prosperity wherever he goes.

He is also associated with generosity, as his bag is said to contain gifts and blessings for those in need. His carefree attitude and contagious laughter make him a beloved symbol of optimism and good fortune.

Hotei is often depicted surrounded by children, reflecting his role as a guardian of innocence and playfulness. Temples and statues dedicated to him are visited by those seeking joy, prosperity, and relief from worries, ensuring his enduring popularity in Japanese culture.

Unlock the Mysteries of Japanese Mythology with Superprof

Superprof is an exceptional platform for anyone seeking to deepen their understanding of Japanese mythology or any other subject. With a vast network of experienced tutors worldwide, Superprof connects students, or enthusiasts, with professionals who specialize in history, culture and language.

Whether you’re curious about the intricacies of Shinto beliefs, the stories behind Japan’s 8 million kami or wish to explore the linguistic nuances in Japanese myths, Superprof offers personalized lessons tailored to your interests and goals! Flexible scheduling, online options and a focus on individual learning needs make it an invaluable resource.

Understanding the role of all 8 million Kami's seems next to impossible. However, proper Japanese lessons can help you learn about critical figures to grasp the essence of Japanese mythology fully!

Very informative ture to its form .

Spot- on: Tenjin (Sky deity).

” In modern-day Japan, students visit the shrine before exams for the blessings of the scholar deity”

Over the 50years our Martial Arts Studets sat written exams and are encouraged to know much more about the Japanese traditions and fine cultures – do research work.

I will qoute your work as a good source.

God bless you.

Kindest regard

Carl-D Hanchi